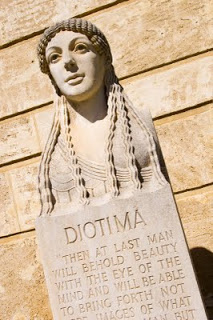

Who was the real Diotima?

Roughly half the characters in my books were real people. Socrates and Pericles were real, obviously, and so too was Diotima, though she's not nearly so well known.

The real Diotima only appears in one place in recorded history, but if you can only make your mark once, you couldn't pick a better place to do it than the most famous book of philosophy ever written: the Symposium, by Plato.

The Symposium is full of interesting stuff, but at core it's a vehicle to let Socrates talk about what is love. Socrates says right away that everything he knows, he learned from Diotima, and he proceeds to relate what Diotima taught him. The Symposium therefore is actually Plato's translation of Socrates' interpretation of Diotima's philosophy. It's interesting too that Socrates recounts the whole thing as a Socratic dialogue in which he's on the receiving end, just for a change.

Socrates introduces Diotima in a way that in the Greek implies there's something salacious in her background, in a nudge nudge wink wink sort of way, which has led some people to think she must have been a courtesan. It's not impossible, but Diotima is definitely not a hetaera name. Courtesans (hetaerae) always adopted a stage name that went with the job description. Diotima is not even close, in fact it's a divine name that means honoured by God. That in turn has led most people to think she was a priestess. Quite a few translations describe her as a priestess, a prophetess or a seer. I covered every base in my books by making her a priestess with something salacious in her background, but not in the way you might expect.

This makes her part of history's most powerful student-teacher chain. Diotima taught Socrates. Socrates taught Plato. Plato taught Aristotle. Aristotle taught Alexander the Great.

The Symposium puts Diotima of Mantinea amongst the top three women intellects of her century, the other two being Gorgo of Sparta and Aspasia of Miletus. (You'll probably get wildly different views from others, but that's the way I see it.) All three women are typically referred to by their place name, as men would be, whereas most women in that age were referenced with respect to the name of their husband or father. Sappho gets the same level of respect.

When Socrates says he was taught by this woman, no one in the room stops Socrates to ask who is this Diotima? It seems everyone knows of her. I get this mental image of the combined intellectual elite of Athens nodding their heads in unison and saying to themselves, "Yep, that Diotima is one smart chick."

Plato only used real people in his books, with only a few minor exceptions, and when there was any doubt to whom he was referring, he'd pop in two lines of explanation. So in another book for example, when Socrates says Aspasia had taught him rhetoric, Plato stops to explain she's the wife of Pericles and the author of his famous Oration for the Fallen. Likewise, with Diotima, he stops to say Diotima was skilled in more than just the philosophy of love, because by instructing the Athenians ten years before the plague, she managed to delay its coming for a decade.

Whoa! The Great Plague of Athens was the single most destructive event in the lives of every man in that room. Every one of them lost close family to the plague, probably every one of them had survived it themselves, possibly a few men present were missing fingers or toes because of it. Yet when Socrates says Diotima held back the plague for ten years, not a single person in the room is surprised, or asks what is this amazing thing she did. They accept Socrates' statement without question. Apparently, it was common knowledge.

Right away, this makes the Diotima-as-courtesan theory look very bad, and the Diotima-as-priestess theory look very good. We don't know what Diotima did, but whatever it was, it must have been spectacular. Probably she performed some sort of ritual, and the Athenians believed she'd been responsible for what was a natural phenomenon. But the mere fact that they thought she was capable of such a thing tells us a lot about her reputation. Another possibility is she instructed the Athenians to perform a regular ritual such as, for example, washing their hands. (This is very much my own speculation, and if true, would require her to have a knowledge of disease vectors far ahead of her time.)

Since she's described as coming from Mantinea, which is a minor city down the road from Athens, that means she must have been a metic. Metics were permanent residents but not citizens. One wonders what goddess she was a priestess of. Aphrodite would be the obvious choice given her subject in the Symposium, but Aphrodite didn't get much airplay in Athens. Athena would be another obvious choice, but Athens of all places didn't need to import a priestess of Athena. We'll never know, so I decided she was a priestess of Artemis. Artemis was surprisingly well served at Athens with three temples, and it seemed so appropriate that a detectrix should be devoted to the Goddess of the Hunt.

The real Diotima only appears in one place in recorded history, but if you can only make your mark once, you couldn't pick a better place to do it than the most famous book of philosophy ever written: the Symposium, by Plato.

The Symposium is full of interesting stuff, but at core it's a vehicle to let Socrates talk about what is love. Socrates says right away that everything he knows, he learned from Diotima, and he proceeds to relate what Diotima taught him. The Symposium therefore is actually Plato's translation of Socrates' interpretation of Diotima's philosophy. It's interesting too that Socrates recounts the whole thing as a Socratic dialogue in which he's on the receiving end, just for a change.

Socrates introduces Diotima in a way that in the Greek implies there's something salacious in her background, in a nudge nudge wink wink sort of way, which has led some people to think she must have been a courtesan. It's not impossible, but Diotima is definitely not a hetaera name. Courtesans (hetaerae) always adopted a stage name that went with the job description. Diotima is not even close, in fact it's a divine name that means honoured by God. That in turn has led most people to think she was a priestess. Quite a few translations describe her as a priestess, a prophetess or a seer. I covered every base in my books by making her a priestess with something salacious in her background, but not in the way you might expect.

This makes her part of history's most powerful student-teacher chain. Diotima taught Socrates. Socrates taught Plato. Plato taught Aristotle. Aristotle taught Alexander the Great.

The Symposium puts Diotima of Mantinea amongst the top three women intellects of her century, the other two being Gorgo of Sparta and Aspasia of Miletus. (You'll probably get wildly different views from others, but that's the way I see it.) All three women are typically referred to by their place name, as men would be, whereas most women in that age were referenced with respect to the name of their husband or father. Sappho gets the same level of respect.

When Socrates says he was taught by this woman, no one in the room stops Socrates to ask who is this Diotima? It seems everyone knows of her. I get this mental image of the combined intellectual elite of Athens nodding their heads in unison and saying to themselves, "Yep, that Diotima is one smart chick."

Plato only used real people in his books, with only a few minor exceptions, and when there was any doubt to whom he was referring, he'd pop in two lines of explanation. So in another book for example, when Socrates says Aspasia had taught him rhetoric, Plato stops to explain she's the wife of Pericles and the author of his famous Oration for the Fallen. Likewise, with Diotima, he stops to say Diotima was skilled in more than just the philosophy of love, because by instructing the Athenians ten years before the plague, she managed to delay its coming for a decade.

Whoa! The Great Plague of Athens was the single most destructive event in the lives of every man in that room. Every one of them lost close family to the plague, probably every one of them had survived it themselves, possibly a few men present were missing fingers or toes because of it. Yet when Socrates says Diotima held back the plague for ten years, not a single person in the room is surprised, or asks what is this amazing thing she did. They accept Socrates' statement without question. Apparently, it was common knowledge.

Right away, this makes the Diotima-as-courtesan theory look very bad, and the Diotima-as-priestess theory look very good. We don't know what Diotima did, but whatever it was, it must have been spectacular. Probably she performed some sort of ritual, and the Athenians believed she'd been responsible for what was a natural phenomenon. But the mere fact that they thought she was capable of such a thing tells us a lot about her reputation. Another possibility is she instructed the Athenians to perform a regular ritual such as, for example, washing their hands. (This is very much my own speculation, and if true, would require her to have a knowledge of disease vectors far ahead of her time.)

Since she's described as coming from Mantinea, which is a minor city down the road from Athens, that means she must have been a metic. Metics were permanent residents but not citizens. One wonders what goddess she was a priestess of. Aphrodite would be the obvious choice given her subject in the Symposium, but Aphrodite didn't get much airplay in Athens. Athena would be another obvious choice, but Athens of all places didn't need to import a priestess of Athena. We'll never know, so I decided she was a priestess of Artemis. Artemis was surprisingly well served at Athens with three temples, and it seemed so appropriate that a detectrix should be devoted to the Goddess of the Hunt.