Xanthippus, the father of Pericles, was a war hero from the time of the invasion of the Persians. In the early stages of the conflict he commanded a trireme.

Xanthippus, the father of Pericles, was a war hero from the time of the invasion of the Persians. In the early stages of the conflict he commanded a trireme.Like any wealthy landholder, Xanthippus owned a hunting dog. We don't know the name of his dog, but we do know they were inseperable. They went to war together, even to sea battles.

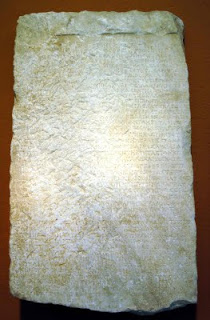

After the Persians broke through at Thermopylae it was clear Athens couldn't be saved. Themistocles, who more or less commanded the Greek forces, ordered the evacuation of the city. Amazingly, his proclamation still exists, inscribed in a stone tablet. Here's a picture from Wikimedia Commons. The authenticity of the tablet is considered controversial by some, but the odds are fair you are looking at the real thing.

After the Persians broke through at Thermopylae it was clear Athens couldn't be saved. Themistocles, who more or less commanded the Greek forces, ordered the evacuation of the city. Amazingly, his proclamation still exists, inscribed in a stone tablet. Here's a picture from Wikimedia Commons. The authenticity of the tablet is considered controversial by some, but the odds are fair you are looking at the real thing.Even with the best preparation, the evacuation of a major city could have been nothing but a shambles. Crowds of people – the whole city, tens of thousands – packed the ports desperate to get away before the Persians enslaved the women and children and killed the men.

The Athenians used their whole fleet, which was the largest in the world, plus anything that would float. Hundreds of boats rowed from the port of Piraeus to the island of Salamis where they had refuge, every trip dangerously overloaded. It was like an ancient version of Dunkirk but with civilians thrown in. Herodotus says it was amazing how few boats capsized.

This was 19 years before the time of my first novel. Nicolaos is 1 year old; Pericles is a boy. They would both have been taken to the relative safety of Salamis. But there weren't enough boats to save everyone. They got away all the able-bodied men, and the women and children who were the future of the city. Then they had to make some hard decisions. Old men, old women, the badly injured and the sick, had to stay behind. There was no room or time.

Xanthippus commanded the last boat out. Probably the Persians were already in the city. The dog of Xanthippus was occupying very little room, but it was room where another man could stand. Xanthippus had to choose between his dog, and saving the life of one more Athenian. He released the dog onto shore and ordered him to run away to the hills, hoping he'd survive. The men began to row. The boat would have been so full the sea lapped at the gunwales. The people left behind would have been wailing and screaming for them to return.

Xanthippus' dog watched his master depart. Then he leaped into the sea, and swam. He caught up the boat and stayed with it, swimming alongside. The people onboard saw what he was doing and shouted encouragement. There's no way a dog should have been able to keep pace with a trireme, but he did. Presumably the load on the trireme was such it could move only very slowly. To swim the distance was impossible, but the dog refused to give up.

The dog of Xanthippus swam all the way from Piraeus to Salamis.

When they got there the dog staggered up onto the beach and collapsed onto the sand, and there, with Xanthippus, he died of exhaustion.

Xanthippus was devastated. He built a tomb for his dog at the place where he died, and ever after, that point on the headland was called Dog's Tomb.

A few days later, in a do-or-die effort, the Greeks crushed the Persian navy in the straits of Salamis.