I'm not sure that anyone really knows where the key and lock were invented. Obviously people have been barring doors from the inside since time immemorial (and is probably the reason why to this day, house doors open inwards). In a world with house slaves you don't need keys and locks very much: the house slave who watches the door (the janitor, in Latin) identifies the visitor and lifts the bar.

The earliest mention of keys that I know of is from Homer, the Odyssey, book 21. Odysseus after one or two adventures has made his way home to discover an annoying number of men trying to marry his wife. Penelope goes to collect her husband's weapons (this will not end well for the suitors).

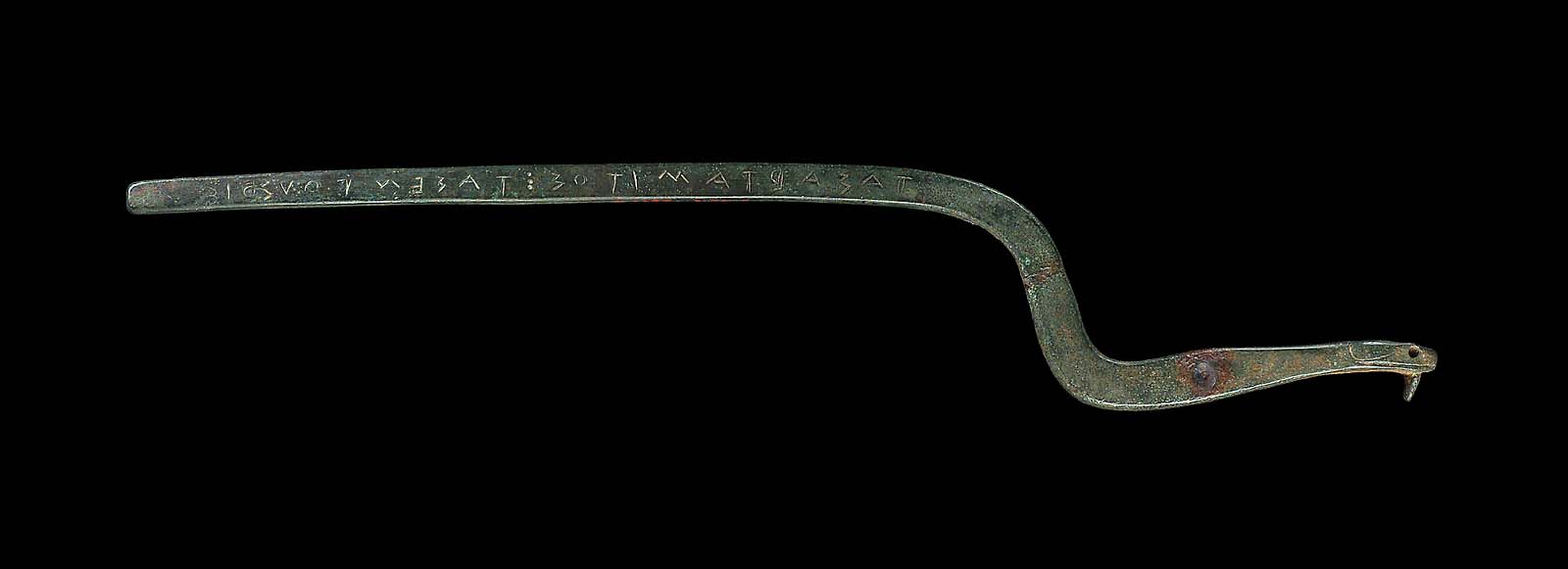

[Penelope] descended the tall staircase of her chamber, and took the well-bent key in her strong hand, a goodly key of bronze, whereon was a handle of ivory.

Here we have a key, at the time of the Trojan War. Given the likely dating on Homer, the year is at least 600BC and probably well before. I want to point out the description of the key as "well-bent", and "bronze". Because in the late 1800s an art collector named Edward Warren, who seriously knew his antiquities, came across this:

credit: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

You can find this interesting item at the excellent Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. It is exactly like the description from Homer. The words inscribed in the bronze identify it as the key for the Temple of Artemis at Lusoi, in Akadia. The difference is, this key is dated to the 5th century BC, which is when Nico & Diotima lived. So this is a key as my heroes would have seen them.

The key fits through a slot in the door, and you then turn it to lift the bar on the other side.

You can forget about carrying ancient keys in your pocket. This thing is more than forty centimeters long. That's about sixteen inches.