Merry asked how I go about doing my book research, especially finding the details of everyday life. So with my vast qualifications firmly in mind, here is the core of how I approach it. I'll do other posts about specific bits later.

I'm going to stick to book research for Classical Greece, because that's what I know, though I imagine the general principles apply to any period.

To start with, a decent knowledge of the histories written by Herodotus and Thucydides is mandatory. They're the Big Two, and if you don't know them then you are doomed. As I write this my copies are within arm's reach, on the shelf above my head.

Herodotus is a fine old chatterbox and reads more like a Boys' Own Adventure than the founding document of history and anthropology. Thucydides is full of geopolitics and is better than any modern thriller.

Both can be mined mercilessly for material. There's a novel on every page. For example you may have heard of a movie called 300. It comes from Herodotus, seriously mangled.

There are two modes of research: trawling and targeted search. Trawling means just wandering about reading stuff, with my radar open for anything I might be able to use.

Targeted search means what it says. The dog breed post was targeted search, but the post about Xanthippus' dog was me remembering something I'd read years ago on a trawl.

Even when doing targeted research it's important to keep your radar open for anything that might be useful. Here's an example I haven't used yet: the people of that time had steam baths using heated stones. I knew that long ago from a trawl. So I decided in my second book, Nico goes for a steam bath in Ephesus. Now I needed minute details of how a Classical Greek steam bath worked. That's targeted search. As I picked up details, I noticed Herodotus idly mentions in passing that the northern barbarian Scythians liked to throw hemp seeds on the hot stones of their baths. Ding! Ding! Ding!

If I ever get Nico up north to Scythia, you know he's going to be having a bath, don't you?

Targeted search often starts with Google but never ends there. Information on the web is, for the most part, highly unreliable. There are wonderful exceptions though. The Perseus database and NS Gill can both be assumed correct. Michael Lahanas is very reliable and a good source of references. But for the most part anything you read needs to be backed by a primary source, which means something written at the time or close thereto, or else by archaeological evidence.

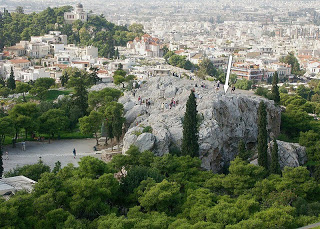

It's surprising how much information about daily life comes from archaeology and not written history. For example, what if your character is putting out the garbage? (In which case the character is certainly a slave.) People at the time never thought to write down where they dumped their rubbish. Archaeologists find the middens so we know most people kept a dump out back. We get house plans, cooking utensils, boat design, weaponry, clothing pins, bronze mirrors, hair combs, assorted pottery, voting tokens, clothing styles, musical instruments, and all sorts of other stuff from archaeology. The Metropolitan, the Louvre, the British Museum and the National Archaeology Museum of Athens are your friends.

Besides the Big Two, there're a host of other contemporary writers with useful things to say. Who you read depends on what you're after, and you just have to know who's who. For anything to do with manly pursuits, Xenophon's your guy. For civic administration, you probably want Aristotle. Besides being hilarious, the comedies of Aristophanes are packed with details of everyday life, especially life's little irritations. For anything to do with the life of Socrates, you definitely want Plato.

Plato's a good example of how to read these sources. He wrote reams of profound thoughts about philosophy. It's all totally useless, to me at least. But he made his philosophy interesting by writing it as dialogues, and in the dialogues the historically real characters make off the cuff comments that are absolute gems to me. When I read Plato, I ignore the signal and read the side-channels.

In a book by Plato called Laches, a character called Lysimachus mentions to Socrates he was a friend of Socrates' father. For Plato, it was a mere opening ploy. But we know the real Lysimachus came from a political family which was closely associated with Pericles. Ding! Ding! Ding! I just found a for-real link between the family of Nico and the family of Pericles. When I discovered this, I wrote an imaginary character out of the book and wrote in the for-real Lysimachus, to give me an historically accurate personal connection.

And that's fundamentally it. The basic rule is: read, keep your radar on, and connect.

I certainly haven't hit every useful text in this post. I'd be interested to know if anyone has other suggestions?

I'm going to stick to book research for Classical Greece, because that's what I know, though I imagine the general principles apply to any period.

To start with, a decent knowledge of the histories written by Herodotus and Thucydides is mandatory. They're the Big Two, and if you don't know them then you are doomed. As I write this my copies are within arm's reach, on the shelf above my head.

Herodotus is a fine old chatterbox and reads more like a Boys' Own Adventure than the founding document of history and anthropology. Thucydides is full of geopolitics and is better than any modern thriller.

Both can be mined mercilessly for material. There's a novel on every page. For example you may have heard of a movie called 300. It comes from Herodotus, seriously mangled.

There are two modes of research: trawling and targeted search. Trawling means just wandering about reading stuff, with my radar open for anything I might be able to use.

Targeted search means what it says. The dog breed post was targeted search, but the post about Xanthippus' dog was me remembering something I'd read years ago on a trawl.

Even when doing targeted research it's important to keep your radar open for anything that might be useful. Here's an example I haven't used yet: the people of that time had steam baths using heated stones. I knew that long ago from a trawl. So I decided in my second book, Nico goes for a steam bath in Ephesus. Now I needed minute details of how a Classical Greek steam bath worked. That's targeted search. As I picked up details, I noticed Herodotus idly mentions in passing that the northern barbarian Scythians liked to throw hemp seeds on the hot stones of their baths. Ding! Ding! Ding!

If I ever get Nico up north to Scythia, you know he's going to be having a bath, don't you?

Targeted search often starts with Google but never ends there. Information on the web is, for the most part, highly unreliable. There are wonderful exceptions though. The Perseus database and NS Gill can both be assumed correct. Michael Lahanas is very reliable and a good source of references. But for the most part anything you read needs to be backed by a primary source, which means something written at the time or close thereto, or else by archaeological evidence.

It's surprising how much information about daily life comes from archaeology and not written history. For example, what if your character is putting out the garbage? (In which case the character is certainly a slave.) People at the time never thought to write down where they dumped their rubbish. Archaeologists find the middens so we know most people kept a dump out back. We get house plans, cooking utensils, boat design, weaponry, clothing pins, bronze mirrors, hair combs, assorted pottery, voting tokens, clothing styles, musical instruments, and all sorts of other stuff from archaeology. The Metropolitan, the Louvre, the British Museum and the National Archaeology Museum of Athens are your friends.

Besides the Big Two, there're a host of other contemporary writers with useful things to say. Who you read depends on what you're after, and you just have to know who's who. For anything to do with manly pursuits, Xenophon's your guy. For civic administration, you probably want Aristotle. Besides being hilarious, the comedies of Aristophanes are packed with details of everyday life, especially life's little irritations. For anything to do with the life of Socrates, you definitely want Plato.

Plato's a good example of how to read these sources. He wrote reams of profound thoughts about philosophy. It's all totally useless, to me at least. But he made his philosophy interesting by writing it as dialogues, and in the dialogues the historically real characters make off the cuff comments that are absolute gems to me. When I read Plato, I ignore the signal and read the side-channels.

In a book by Plato called Laches, a character called Lysimachus mentions to Socrates he was a friend of Socrates' father. For Plato, it was a mere opening ploy. But we know the real Lysimachus came from a political family which was closely associated with Pericles. Ding! Ding! Ding! I just found a for-real link between the family of Nico and the family of Pericles. When I discovered this, I wrote an imaginary character out of the book and wrote in the for-real Lysimachus, to give me an historically accurate personal connection.

And that's fundamentally it. The basic rule is: read, keep your radar on, and connect.

I certainly haven't hit every useful text in this post. I'd be interested to know if anyone has other suggestions?