How hard would it be to practice the ancient Greek religion these days?

Yes, I'm aware there are people doing their own modern versions of the ancient worship, but I'm talking about worshiping the Gods and Goddesses as it was done back in the good old days; done so well that an ancient Greek transported 2,500 years into the future would recognise his own religion.

The answer is: very tough indeed.

To start with, if you're not sacrificing animals, then you're just not doing it right.

Sorry, but that's the way it is. Animal sacrifice is central to ancient religion but anathema to virtually anyone practicing modern paganism. I certainly wouldn't condone it; it would probably be illegal in most countries; but if you want to do religion the way the Greeks did then you don't have a choice. Every important ritual and festival required a sacrifice, and an important element was that the sacrifice "agree". It's fine to have a BBQ afterwards, but you'll need some butchering skills which aren't exactly common these days.

You need an almost encyclopaedic knowledge of Homer.

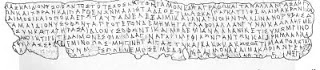

The Greeks had no Bible. Their entire written experience of the Gods came from Homer, and from another ancient author called Hesiod, who amongst other things wrote Theogeny, which defined the relationships between the Gods and Goddesses.

At heart the Greeks expected the Gods to behave the way Homer wrote them. It's as if we took our Christian viewpoint from Shakespeare.

Learn a lot of hymns and odes.

Actually this is good news, because most of them are very good. There were a whole pile of standards and favourites, which when you get down to it is the same as having psalms. The difference is you need to memorize a few thousand lines, because normal people didn't have books with this stuff written in. Not to worry, you'll have plenty of time to memorize while the building work is underway.

You need a cult statue. And a temple.

The Greeks did almost everything in the open air. Except religion. For that they built very elegant, very expensive temples. Inside each temple is a cult statue. The Greeks believed -- and I mean believed -- that the God or Goddess would inhabit the cult statue from time to time. (If a statue transforming into a God seems strange, consider the premise behind the Christian mass. It's called transubstantiation.)

So you need to get together with some friends and buy some decent land. Put a Greek temple on it. The design is very well known but it's a non-standard form these days so the material and labor might be a trifle expensive.

When you've finished the temple hire the best sculptor you can afford for the cult stature. Something ten times larger than life in ivory, gold and silver would be just great, but if that's outside the budget, you may have to settle for a lifesize marble or a cast bronze.

Did I mention you have to do one of these statue/temple combos for each God?

You don't need every minor deity, but you definitely have to cover all the majors. That's Zeus, Hera, Apollo, Athena, Aphrodite, Artemis, Demeter, Dionysus, Hephaestus, Ares, Hermes and Poseidon. Don't forget any of them; not if you know what's good for you, because these guys are known for the odd spot of jealousy, they're easily offended, and they can do serious damage. Ask any Trojan.

Yes, I'm aware there are people doing their own modern versions of the ancient worship, but I'm talking about worshiping the Gods and Goddesses as it was done back in the good old days; done so well that an ancient Greek transported 2,500 years into the future would recognise his own religion.

The answer is: very tough indeed.

To start with, if you're not sacrificing animals, then you're just not doing it right.

Sorry, but that's the way it is. Animal sacrifice is central to ancient religion but anathema to virtually anyone practicing modern paganism. I certainly wouldn't condone it; it would probably be illegal in most countries; but if you want to do religion the way the Greeks did then you don't have a choice. Every important ritual and festival required a sacrifice, and an important element was that the sacrifice "agree". It's fine to have a BBQ afterwards, but you'll need some butchering skills which aren't exactly common these days.

You need an almost encyclopaedic knowledge of Homer.

The Greeks had no Bible. Their entire written experience of the Gods came from Homer, and from another ancient author called Hesiod, who amongst other things wrote Theogeny, which defined the relationships between the Gods and Goddesses.

At heart the Greeks expected the Gods to behave the way Homer wrote them. It's as if we took our Christian viewpoint from Shakespeare.

Learn a lot of hymns and odes.

Actually this is good news, because most of them are very good. There were a whole pile of standards and favourites, which when you get down to it is the same as having psalms. The difference is you need to memorize a few thousand lines, because normal people didn't have books with this stuff written in. Not to worry, you'll have plenty of time to memorize while the building work is underway.

You need a cult statue. And a temple.

The Greeks did almost everything in the open air. Except religion. For that they built very elegant, very expensive temples. Inside each temple is a cult statue. The Greeks believed -- and I mean believed -- that the God or Goddess would inhabit the cult statue from time to time. (If a statue transforming into a God seems strange, consider the premise behind the Christian mass. It's called transubstantiation.)

So you need to get together with some friends and buy some decent land. Put a Greek temple on it. The design is very well known but it's a non-standard form these days so the material and labor might be a trifle expensive.

When you've finished the temple hire the best sculptor you can afford for the cult stature. Something ten times larger than life in ivory, gold and silver would be just great, but if that's outside the budget, you may have to settle for a lifesize marble or a cast bronze.

Did I mention you have to do one of these statue/temple combos for each God?

You don't need every minor deity, but you definitely have to cover all the majors. That's Zeus, Hera, Apollo, Athena, Aphrodite, Artemis, Demeter, Dionysus, Hephaestus, Ares, Hermes and Poseidon. Don't forget any of them; not if you know what's good for you, because these guys are known for the odd spot of jealousy, they're easily offended, and they can do serious damage. Ask any Trojan.